For the longest time, I associated space opera with one thing: big space battles. I may well have gotten that impression before I ever heard the term “space opera.” My parents let me watch the Star Wars movies when I was around kindergarten age (I have a distinct memory of finding the bit with Luke’s hand terrifying, thanks so much, Mom and Dad!). Even later, when I started reading science fiction and fantasy in middle school, book cover illustrations told me that you couldn’t have a space opera without big space battles in them somewhere.

Time passed. I read more space operas: Debra Doyle & James D. MacDonald’s Mage Wars series, Jack Campbell’s Lost Fleet series, Lois McMaster Bujold’s Vorkosigan Saga, Simon R. Green’s Deathstalker Saga, Alistair Reynolds’ Revelation Space, Peter F. Hamilton’s Night’s Dawn series, David Weber’s Honor Harrington series, Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game, James S. A. Corey’s Leviathan Wakes, Ann Leckie’s Imperial Radch trilogy… This isn’t an attempt at a comprehensive or “best” list, and indeed, some famous examples are missing by virtue of the fact that I have never read them (notably Frank Herbert’s Dune and Vernor Vinge’s A Fire Upon the Deep).

Big space battles continued to be a feature, yes. But I noticed that some space operas had a difference of emphasis when it came to those battles. In some of them the big space battles were foregrounded, just as future tank warfare is foregrounded in David Drake’s The Tank Lords—if you’re not interested in hardcore tank action, you might as well not read that book. (I was very much interested in hardcore tank action.) In others, the big space battles were not the focus—or anyway, not the only focus.

What do I mean by this? Let’s take a TV show that has (to my knowledge) nothing to do with space or battles, Suits. Suits is ostensibly about lawyers, plus a protagonist, Michael Ross, who is faking being a lawyer with the aid of an actual lawyer. The show uses the furniture of lawyerhood in a handwavey sort of way as a backdrop for its storytelling and characters. However, the real-life lawyers of my acquaintance I mentioned the show to grimaced and said they couldn’t stand the show.

Suits isn’t really about lawyers, see. (At least, I hope in real life no one would be able to get away with being a fake lawyer as long as Mike Ross does?) It’s about other things: Mike Ross’s ethical dilemmas as he hustles to provide for his ailing grandmother; the tension between lawyers Harvey Specter, who is hiding Mike’s secret and conspiring with him, and Harvey’s rival Louis Litt. All the lawyer business is just backdrop for interpersonal drama.

Similarly, you can have space opera where the genre furniture—the big space battles and weapons of ultimate destruction and larger-than-life heroes—is played straight, where it’s the main focus of the narrative. Jack Campbell’s Lost Fleet is a great example of this. While we do get some character development for the protagonist, Black Jack Geary, most of the story (at least through the first five books) concerns desperate fleet actions against long odds. Worldbuilding is fairly minimal. There are a few indications of culture, such as a belief that the stars are ancestors, but they are vestigial compared to the loving descriptions of (you guessed it) big space battles. That’s not a criticism, by the way. I really enjoyed these books for their combination of action and high stakes.

Simon R. Green’s Deathstalker Saga is another example of space opera where the focus is on going all-out with familiar tropes. The series features a historian with hidden superpowers turned reluctant hero and revolutionary, a lady gladiator, an android, and more oddball allies facing espers (people with psi powers), superintelligent AIs, and, of course, the forces of an evil empress. The result is a no-holds-barred narrative that relies on well-known space opera furniture alongside a fast-paced plot.

But other space operas use those tropes in the background, where they use them at all, and instead emphasize the creation of strange new worlds and societies. One recent example is Ann Leckie’s Imperial Radch series. The first and third books feature some space combat, but I would be hard pressed to say that the space combat is the most noteworthy part of those stories. Rather, what I remember from those books are the repurposed corpses (“ancillaries”) used as meat puppets by ship AIs, and the imperialistic culture of the Radch, and of course the protagonist of the trilogy, a former ship’s ancillary on a quest for vengeance. The experience of reading this trilogy depends strongly on the reader’s understanding of the unique society that the characters move through.

Lois McMaster Bujold’s Vorkosigan Saga is another space opera where the setting’s sociocultural backdrop, particularly that of the quasi-feudal, militaristic world of Barrayar, heavily informs the story and the lives of its characters. When I think about those books, the personalities of the characters blaze brightly in my memory, as well as the clash of cultures and values, starting with Cordelia Naismith’s encounter with the Barrayarans and continuing through the following generations. I don’t really remember the space battles in their own right; rather, I think of them through the lens of their political significance to the characters, if at all.

Thinking about space opera (or indeed any other genre) solely in terms of its common tropes is limiting. While there’s nothing wrong with works that simply adhere to those tropes, whether of background or characters or plot, it’s a lot of fun to read works that use those elements as a backdrop to something bigger. Even a space opera can be about more than big space battles!

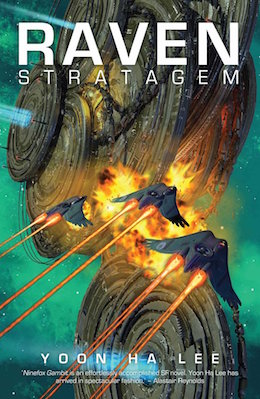

Yoon Ha Lee’s space opera novel Ninefox Gambit is available from Solaris Books; its sequel Raven Stratagem publishes June 13th. He lives in Louisiana with his family and an extremely lazy cat, and has not yet been eaten by gators.

Yoon Ha Lee’s space opera novel Ninefox Gambit is available from Solaris Books; its sequel Raven Stratagem publishes June 13th. He lives in Louisiana with his family and an extremely lazy cat, and has not yet been eaten by gators.